Your guide correctly identifies critical situations where ginger—often hailed as a universal remedy—requires caution or avoidance. While ginger is a potent anti-inflammatory and digestive aid for most, its pharmacologically active compounds (gingerols, shogaols) can interact with certain health conditions and medications. Let’s refine this into an actionable, evidence-based reference.

The 5 Health Conditions That Require Ginger Caution

The 5 Health Conditions That Require Ginger Caution

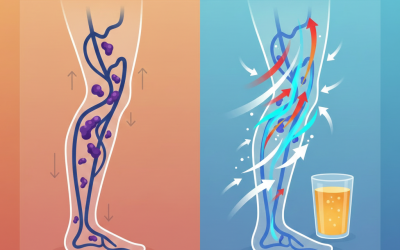

1. Bleeding Disorders & Anticoagulant Therapy

-

The Risk: Ginger inhibits thromboxane synthase (a clotting factor) and platelet aggregation. This potentiates the effect of blood thinners like warfarin (Coumadin), apixaban (Eliquis), clopidogrel (Plavix), and even daily aspirin.

-

Evidence: Clinical studies show ginger can increase INR (a measure of blood clotting time) in patients on warfarin.

-

Action Plan:

-

Avoid medicinal doses (supplements, concentrated extracts, daily large quantities in food).

-

Small culinary amounts (e.g., a few slices in stir-fry) are likely safe but must be cleared by your hematologist or cardiologist.

-

Safer Alternatives: For anti-inflammatory benefits, consider turmeric (curcumin) in moderation, but note it also has mild antiplatelet effects. Vitamin K-rich foods (leafy greens) support healthy clotting.

-

2. Diabetes on Medication (Hypoglycemia Risk)

-

The Risk: Ginger enhances insulin sensitivity and may stimulate glucose uptake, potentially causing dangerous lows (hypoglycemia) when combined with insulin or sulfonylureas (e.g., glipizide, glyburide).

-

Evidence: Multiple animal and some human studies confirm its hypoglycemic effect.

-

Action Plan:

-

Monitor blood glucose closely if consuming ginger regularly.

-

Inform your doctor to adjust medication if needed.

-

Consume with meals to buffer its effect.

-

Safer Alternatives: Cinnamon (Ceylon variety) has a more studied and gentle modulating effect on blood sugar. Fiber-rich foods (psyllium, legumes) help stabilize post-meal glucose spikes.

-